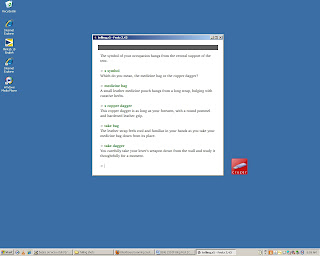

For me, interacting with this piece of hypertext was difficult, mainly because it is a non-linear text, and so the plot is not as easy to follow. Jackson created this piece in a manner that would force readers to piece the story together themselves, as Patchwork Girl informs interactors when she says “If you want to see the whole, you will have to piece me together yourself” (Jackson). In “Gathering the Limbs of the Text in Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl,” authors Carolina Sánchez-Palencia Carazo and Manuel Almagro Jiménez note that “Patchwork Girl is not simply one more text that reflects the aesthetics of fragmentation and hybridity; it is a hypertext that allows for material and technological possibilities that would be unthinkable in a printed version. As a consequence, the relationship between reader and text also becomes provisional and mutable inasmuch as different possible readings arise: one ordered, as in the chart view, and another chaotic or random-like, simply by clicking on any word in a given lexia” (Carazo et al. 116). As a side note, readers should keep in mind that Patchwork Girl (the disc) is for Windows and Mac, not Linux-- if you are a Linux user, you're going to need to get to your local library or campus computer lab so you can open the file. When first opened, readers are presented with three windows: one blank page that acts as a background on which users can arrange different, smaller windows with lexia or images; another window titled “her” holds an image of a young girl standing in a posture that slightly resembles Leonardo daVinci’s Vitruvian Man, though this image is sectioned off with dotted lines; the last window, titled “Storyspace Map” shows a chart that begins with “her,” and flows down to “title page,” among other things that eventually lead to the journal, graveyard, body of text, crazy quilt, and story, which contain the pieces that create the Patchwork Girl and her story (see fig. 1).

(fig. 1)

(fig. 1)

Clicking the “title page” opens a new window that contains just that; here, the difference from other title pages (and texts) begins to display itself. The title page credits the authors as being “Mary/Shelley, & Herself” (see fig. 2). This may confuse interactors initially, but as they work through the hypertext, they will realize that this is a valid byline; as I also explored the text and learned about the Patchwork Girl and her creator, I found that while Shelley Jackson created the piece about the Patchwork Girl and her creator/lover, the Patchwork Girl seemed to speak for herself and author her own text, as did Mary Shelley through her original text, Frankenstein. Carazo and Jimenez add that “[t]his deliberate confusion about authorship is also detected in the diversity of sources and borrowings from the literary tradition. Thus, a sample list might include those from her literary mother, Mary Shelley (journal), theorists such as Derrida (sources), not to mention the original owners of the monster’s implants presented in the shape of memories and testimonies, particularly the whole graveyard section…” (Carazo et al. 120). Below the authors’ names are five “pieces,” as I will refer to them, that help interactors begin their hypertextual exploration: a graveyard, a journal, a quilt, a story, & broken accents. Clicking on “a graveyard” opens another window, titled “hercut4” (see fig. 3).  (fig. 2)

(fig. 2)

Clicking the different images in “hercut4” bring up a small window with the lexia that appears to best describe this text, as well as its theme of resurrection: “I am buried here. You can resurrect me, but only piecemeal. If you want to see me whole, you will have to sew me together yourself” (see fig. 4).  (fig. 4)

(fig. 4)

Clicking on “a journal” brings up pieces of lexia from the journal Mary Shelley wrote in while creating and living with the Patchwork Girl. Here, readers discover the fictional Mary Shelley writing about her creation similar to how Dr. Frankenstein wrote about his monster; the difference between these two characters, however, is that Dr. Frankenstein immediately distances himself from his creation, calling it a monster and abhorring it from its first living seconds, whereas Mary Shelley finds beauty in the non-traditionally beautiful being she has created, eventually coming to love her fiercely and have a relationship with her (see fig. 5 and fig. 6).  (fig. 5)

(fig. 5)

In “Gathering the Limbs of the Text in Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl,” Carolina Sánchez-Palencia Carazo and Manuel Almagro Jiménez analyze the various pieces that come together to form the body of text that is Patchwork Girl as well as the main character herself. They assert that interacting with the text “turns readers into a sort of Dr. Frankenstein putting together the different pieces of the textual corpus, and thus creating [their] own monstrous, aberrant reading (Carazo et al. 116). Sometimes, I found it easier to explore by referring back to the Storyspace Map and clicking on boxes there.

Clicking on “body of text” opens a window with a whole new flow chart, containing pieces of lexia like “dreams,” “blood,” and “now” (see fig. 7). Clicking on “story” does something similar, though there are much fewer new boxes for readers to explore. One time during my exploration, I clicked on a box titled “M/S” which then opened up even more pieces of lexia, such as “birth,” “a promise,” “I am,” and “she” (see fig. 8). As I explored and mentally assembled the various pieces of patchwork lexia I encountered, I was able to experience the lives of many women, not just the Patchwork Girl or the fictional Mary Shelley; I was also able to experience the lives of the women whose body parts composed the Patchwork Girl. I think that this is part of Shelley Jackson’s purpose for this text; as we read and interact with Patchwork Girl, we not only resurrect her body, we resurrect the lives of those who created her, as well as the lives of the women in Shelley’s Frankenstein, who are destroyed throughout the course of the novel, including the original female monster created for Dr. Frankenstein’s bastard child/monster. This theme of resurrection helps readers see and appreciate the lives of the women in the text, and how Jackson uses this text to give life to more than one woman silenced or ignored, something even more significant when readers consider the fact that Mary Shelley initially published Frankenstein under her husband’s name, rather than taking credit for such a masterpiece herself for fear of rejection by the patriarchal society she lived in. (fig. 7)

(fig. 7)

Carazo and Jimenez argue that in Patchwork Girl, “Jackson questions the concept of authorship, origin(ality) and literary property, and related issues such as intertextuality and assemblage, all of which are indices of the theoretical concerns underlying Jackson's text and of the ways in which it follows, re-writes or invites us to re-read Shelley's “hideous progeny”” (Carazo et al. 115). Through this, readers are made aware of not only a basic plot within Patchwork Girl, but also the purpose of the many paths readers may choose to pursue in assembling the pieces of the Patchwork Girl and her story. By pushing readers to question the concept of authorship, Jackson shows them just how any text can be a patchwork creation, made up by voices and opinions of many, though attributed to just one voice or author; Jackson may have created the fictional Mary Shelley, but Shelley created Frankenstein, which lent itself to Jackson in creating the various scraps of lexia that became the Patchwork Girl, and the Patchwork Girl developed her own voice throughout the text in a way that separated her from Shelley and Jackson, giving the text an even deeper meaning as the Patchwork Girl and the women who lent their body parts to her share their experiences.

Carazo , Carolina Sánchez-Palencia and Manuel Almagro. “Gathering the Limbs of the Text in Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl”. ATLANTIS. June 2006. 115-129.

Jackson, Shelley. Patchwork Girl. Watertown, MA: Eastgate Systems. 1995.